Goldfields Getaway

27 April, 2021

Dust storms and puddlers

The next-door neighbours were Italian/Australian and weren’t allowed to have guns during the war, so when they wanted to kill a pig, they would ask Grandad. Of course, us kids weren’t allowed anywhere near it, so we’d get up on the roof of the...

Local historian Judith Healey shares her memories of growing up in an extended family in regional Victoria and reflects on the challenges faced by her ancestors as they raised children at the height of the goldrush in the Central Goldfields.

Mildura

My father died when I was little and my mum worked at the hospital as a theatre sister and worked different shifts. So, until I was about 10, I was raised by my grandparents on a farm in Mildura. I can remember Mum coming home at different times and she always had these lovely soft cool hands.

My grandparents were the complete framework of my life when I was little. They were really ordinary, old fashioned people. There were certain things you had to do and it was part of the whole fabric of life.

Growing up with them is where I got the values and social mores that have stayed with me my whole life. You didn’t discuss money, and the only people you didn’t mix with were people that drank and didn’t behave themselves in public. Even today, at my age, I still feel guilty going into a hotel because I think Granny will tap me on the shoulder and tell me off.

We thought it was a wonderful childhood, we didn’t know that there was a difference in people being poor, that was never discussed.

Although they had electricity, Granny always had the wood stove because we had the Mallee roots in Mildura.

All the cooking was done on a wood stove. Granny had a large pot she would make soup in, so nearly all the winter you would be able to have a bowl of soup whenever you wanted. By putting the pots in certain places on the stove they stayed warm or boiled madly, whichever. Women had the arranging of the fire down to a fine art. They knew if they put a certain size log on at whatever time how long it would stay hot for and what they could cook. The wood stove would have been going all winter and we had the wood fire in the lounge.

All of the washing was done in a copper and a wash trough. Granny would light the fire underneath a big copper bucket and fill that with water and soap. When the copper boiled, she put the clothes in. Then she would haul the washing out, rinse them off and the special whites – going-out whites like shirts and blouses – used to get this blue put in them. Then Granny would rinse again, hang them to dry and iron them. And woe betide if there were any marks!

Granny had flat irons and then she got this one they put coals in. You would get the coals out of the fire and open the lid and fill it full of coals, that was a bit flash.

Groceries and meat would be delivered. A man would bring the groceries like biscuits, tea, coffee and sugar, and the butcher would come in a little covered car. He had all the animal carcasses hanging in the back of the van and he’d chop off the leg or whatever you wanted then Granny would have it on a plate covered in a tea towel and put it in the ice chest.

We had an ice chest that was a bit taller than table height. They were generally made of wood and you lifted the lid up; the top was lined with tin with holes in the bottom. A man would come and put a big block of ice in it and you would shut the lid and it would last about a week before it melted. Us kids used to get into trouble because we’d drink the water.

I remember some wonderful teas on a Saturday night when all the different aunts would arrive. I realise now it was mostly aunts because the uncles were away at the war.

The table would be full and there would be about four stands with cakes on them, big cream cakes, and scones and two big legs of lamb. In the summer they were served cold and we’d have wonderful salads.

Another time the women would all get together was to pick the fruit. In those days most of the farmers had fruit trees – almonds, apricots, plums, olives – around their fence line. When it was time, the women would come together and help each other pick all the fruit. Some of them dried the fruit and some of them packed it in boxes and sent it to Melbourne and that was their personal ‘pin’ money.

They grew grapes and fruit on the farm and Grandad didn’t have a tractor. He had a horse and cart and we’d go into town every so often and get bags of chaff and stuff for the horses, all that heavy farm stuff. We thought it was wonderful, you were really grown up when you were allowed to hang your legs over the side.

I can remember Uncle Reggie came out to visit with his first motor car. That would have been in the mid-40s. He came out with what I know now was an Austin 7, a little green thing. We thought it was the funniest thing when Grandad got in it – he was six-foot-five and he was all folded up in this little car.

Another exciting thing I remember was the dust storms. It was a big deal; everyone would run around saying “There’s going to be a dust storm”. We would have to get busy putting towels and blankets on the doors and on the windows. It would get dark in the middle of the day and the sky would go red.

I don’t know how long it would last but Granny used to play the gramophone to keep us amused, so we didn’t mind it at all, we weren’t frightened. Then, when it was over, we had to go outside and sweep all the dust of the veranda. We used to take the mats outside and beat the living daylights out of them with this special shaped stick.

We had a radio and it was a big deal to sit on Grandad’s knee and listen to the news – the whole world had to be quiet while he listened. He’d growl about the different politicians the same as the grandads do now.

The next-door neighbours were Italian/Australian and weren’t allowed to have guns during the war, so when they wanted to kill a pig, they would ask Grandad. Of course, us kids weren’t allowed anywhere near it, so we’d get up on the roof of the shed and lay down and watch.

We thought it was marvellous. We would see the grandfathers and the husbands and men all running around chasing the pig. Then Grandad would shoot it and the Italian grannies and women would butcher it and hang up all the sausages and salamis.

Although times were hard, people didn’t know any different.

The Goldfields

Many years later, when my children were grown and raising their own families, I started researching our family history. I got back as far as Ann Smith (nee Hempsall), my grandad’s grandmother. By going through the church records, rates and newspapers at the time, I have put together some of the life of my grandmother three times back.

Ann came out here as a migrant to Western Australia in 1841, got off the boat and got married. It didn’t seem to be very long before she had a baby, my great grandmother. Between the time she was married to 1851, she had five children and then moved to Victoria.

The family came by boat from Western Australian. Another baby was born when she got off the boat in Melbourne. Then the whole family trundled up here to Central Victoria.

They had to walk, there were no trains or buses in those days. They had six children and she was pregnant again. They stopped in Castlemaine for a little while because the priest there did the baptism for a few of the children.

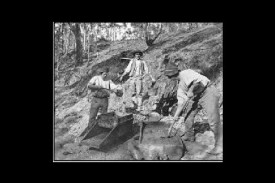

She was one of thousands of people who travelled to the goldfields in the1850s.

Near the railway crossing by the old mill in Maryborough, off to the side it looks like a little lane, but it’s actually a creek. And that creek goes right out nearly to Talbot. Ann, her husband and all the children followed the creek out Amherst way to Blackman’s Lead and stayed there for 20 odd years.

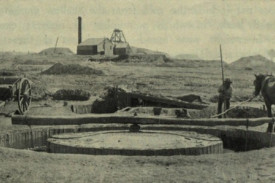

The family lived there in a tent and the husband and oldest son became prospectors. They also had a puddling machine. Prospectors would pay them to wash a load of dirt in the puddler to get the gold.

Everybody lived in tents for about 25 years. On the rates it says ‘wooden walls’ or ‘mudbrick walls’ and brush roof -–what we would call a tent but was probably oiled sail cloth. That was all there was, there was no sheets of tin and no Mr Mitre 10 to go to.

So Ann raised her children there and half the town now is related to one of her daughters. One daughter made my lot, the other daughter made a lot up at Charlton and the other daughter made a huge family in NSW.

We can only imagine what life was like as she raised her family, although there are some written records that have survived. We know that none of her children died of starvation, which was acommon cause of death in those days. On the rates notice it says the house was mudbrick walls with a tarp roof. They didn’t have what were called American stoves inside the house, so she had to cook outside.

There is also a record of her being asked to testify at the inquest into the death of a neighbour who got drunk and beat his wife. His adult son saw what was happening and clouted him over the head with a lump of wood. The man then went to bed and died. The son got the blame for it, but the inquest found he didn’t deliberately try to kill him.

Ann gave evidence that she ‘took the children for a Sunday walk’ while the row was happening. The descendants of that man still live in Maryborough today.

Ann died in 1875 in Blackman’s Lead. She is buried in Maryborough Cemetery along with some of her daughters. Her husband and a few of the children packed up and went up to Charlton.

Unless they wanted to work in the deep lead mines there weren’t all the factories and things to work in. The main objective wasto earn enough money to buy land,unless they were involved in a town type of business – butcher, baker, dressmakers, furniture shops and things like that.

When I started doing my history, I asked Grandad why he never went back to the area where he grew up. He said “Oh no, it’s full of holes, terribly dangerous”. At the timeI didn’t know what he meant. I know now. Even in recent times there have been terrible accidents, not just people falling down the holes but being overcome by the gas.

In the 60s they were putting sewerage into Maryborough just near the railway crossing. The workers parked a bulldozer and left it overnight, when they came back the next day it had gone – fallen in a hole.

It just shows that the history of the goldfields is still there. You might not be able to see it straight away, but sometimes you just need to know where to look.